Don't forget to follow THTFantasy on Twitter. A special shout-out thanks to Yizhe Shen for helping me compile the data for players on multiple teams this year.

Each of the past two seasons, I have made it a habit to use The Hardball Times' expected BABIP (xBABIP) formula in an attempt to take a somewhat luck-neutral look at batting lines from the previous year to help better forecast relative value for the (ages away) upcoming season. Not to break habit, what follows is a breakdown of 2011 batting lines.

Before I present the data, which can be accessed and sorted by clicking here, let me explain my methodology and the crucial-to-understand underlying assumptions. If you have not yet read Chris Dutton and Peter Bendix's article on their xBABIP formula, I suggest doing so before proceeding, because I use their formula.

Step one is calculating each player's xBABIP. This can be done through a variety of methods, but as I have indicated above, I use Chris Dutton and Peter Bendix's xBABIP formula. It is worth noting that other xBABIP formulas do exist, such as the one posted by slash12 a couple of years ago on Beyond The Boxscore. xBABIP is a theoretical model, and each formula has its own pros and cons.

I prefer to use The Hardball Times' version because 1) I'm a company man and 2) it accounts for park (though admittedly, the park factor data are a few years old now, and for a few teams—the Yankees, Twins, Mets, and starting next year, the Marlins—the park factors are entirely obsolete). Feel free to use the follow methodology of determining batting line with whatever formulation of xBABIP you choose.

Once you have calculated each player's xBABIP (a feat easier said than done, especially if you have to account for partial seasons and league/park factors), you will need to apply it using fancy algebra to determine a player's expected, luck-neutralized batting average (xAVG), on base percentage (xOBP), and slugging percentage (xSLG).

To calculate expected batting average, you begin by calculating the expected hits differential between a player's actual BABIP and his expected BABIP. To calculate a player's expected hits total, simply rearrange the BABIP formula using xBABIP in place of actual BABIP.

In other words, a player's expected hits are equal to that player's actual home run total plus his xBABIP times the following: At-bats minus strikeouts minus home runs plus sacrifice flies. In other words, xH=HR+xBABIP*(AB-K-HR+SF). Take this expected hits total and divide by at-bats to get xAVG.

Next, you will need to calculate xOBP. This is done by simply taking the quotient of the sum of hits, walks and hit by pitches and dividing that by the sum of at bats, walks, hit by pitches, and sacrifice flies. Not too complicated.

Calculating xSLG is at least as easy as calculating xOBP, but how you calculate it largely depends on how you perceive xBABIP to affect hits. If you think that a player's power rate would remain constant irrespective of BABIP luck, then you simply calculate a player's actual ISO (slugging percentage minus batting average) and add that value to his expected batting average.

If you pessimistically/optimistically believe that all hits gained/lost to BABIP luck were singles, then you calculate xSLG as by adding the difference between expected hits and actual hits to a player's singles total, and then dividing the sum of singles plus two times doubles plus three times triples plus four times home runs by at-bats.

As may be obvious, both methods have their own issues with calculating the expected power of the hits gained/saved through BABIP luck.

The first xSLG method holds power constant, which seems nice in theory. However, given that home runs totals are generally not affected by BABIP luck hit changes, using ISO either over/underestimates power depending on whether xBABIP would either subtract or add hits to a player's final line.

With the hits-added method, a player would be adding non-home run hits at an ISO pace that includes home runs. Alternatively, if hits are subtracted, it is subtracting some home run power value.

The "be overly pessimistic/optimistic approach" of course greatly oversimplifies this error, but it does so with a degree of skepticism. For hits added, we see what life would be like if all hits were singles, and think that there's power upside to be had in the projection.

Alternatively, for hits subtracted, we get some dose of reality with the understanding that there's a little more risk than the downward adjustment the numbers indicate. You might think of a hits-subtracted situation assuming all singles as the "upside" of luck-adjustment.

So pick you method of xSLG; each has its own vices. I prefer to use the first method (constant ISO adjustment), so that is what you will find in my spreadsheet of numbers below.

The methodology laid out, there are a few crucial points that must be addressed before the data are presented.

First is the people included in my data set. My data address only players who accumulated 300 or more plate appearances. With the exception of infield flyballs, pretty much all of the rest of the relevant xBABIP data stabilize by a half season's worth of plate appearances.

However, several players of interest were fewer than 15 plate appearances under the threshold (Desmond Jennings, Justin Morneau, Grady Sizemore, Chris Coghlan and John Mayberry) who I decided to add to the sample out of personal interest nonetheless.

Second, you are probably wondering how to use a different xBABIP formula (particularly slash12's) to get all the relevant numbers without having to do any additional, unnecessary work on your own. As a guy with a background in economics, I understand that desire to do the least amount of additional work necessary to capture the benefit sought, and accordingly, making an xBABIP formula adjustment is very easy with my spreadsheet.

All you need to do is change the formula in the xBABIP cell for the first player to reflect your favored xBABIP formula. Then, drag that cell down vertically to the bottom of the data set. Voila! All of the resulting changes and math will be done for you.

Finally, it is worth reminding you that the default xBABIP method used in my spreadsheet has slightly obsolete data (it's multi-year data from a couple of years ago) that is totally obsolete with respect to a few teams: The Mets, Yankees and Twins. With these three teams, you will need to mentally adjust the numbers to reflect the differential between these teams' old parks and their new ones.

Beyond just the limits of my particular data set, there is also an important assumption that underlies xBABIP that is critical to note. This assumption—which will be true of any xBABIP formula (well, unless that formula regresses a player's numbers towards some skill-based mean, which in and of itself would raise its own issues)—is that a player's xBABIP from year N will remain constant in year N+1. This is a bold assumption, and highly unlikely to be true in any single case.

xBABIP analyzes past luck based on past results, but it does not forecast the underlying elements that go in to figuring out the difference between skill and luck-based reality for future situations. To the extent a player's expected future walk rate, strikeout rate, groundball rate, flyball rate, infield flyball rate, line drive rate and home run rate—to name a few areas—could/will deviate next year from this year, xBABIP will not reflect those deviations.

Hence, if you think a player's line drive rate will increase in 2012 compared to 2011, then you should assume that his real expected future BABIP will be higher than his xBABIP. Let's call this difference nominal xBABIP and real xBABIP.

You should be particularly wary of players who had abnormally high/low home run rates last year. To the extent that home runs will increase or decrease in 2012, that will be a major factor that will impact the player's real versus nominal xBABIP figure. My spreadsheet calculates nominal xBABIP and makes adjustments accordingly. You will need to calculate or mentally adjust real xBABIP on your own.

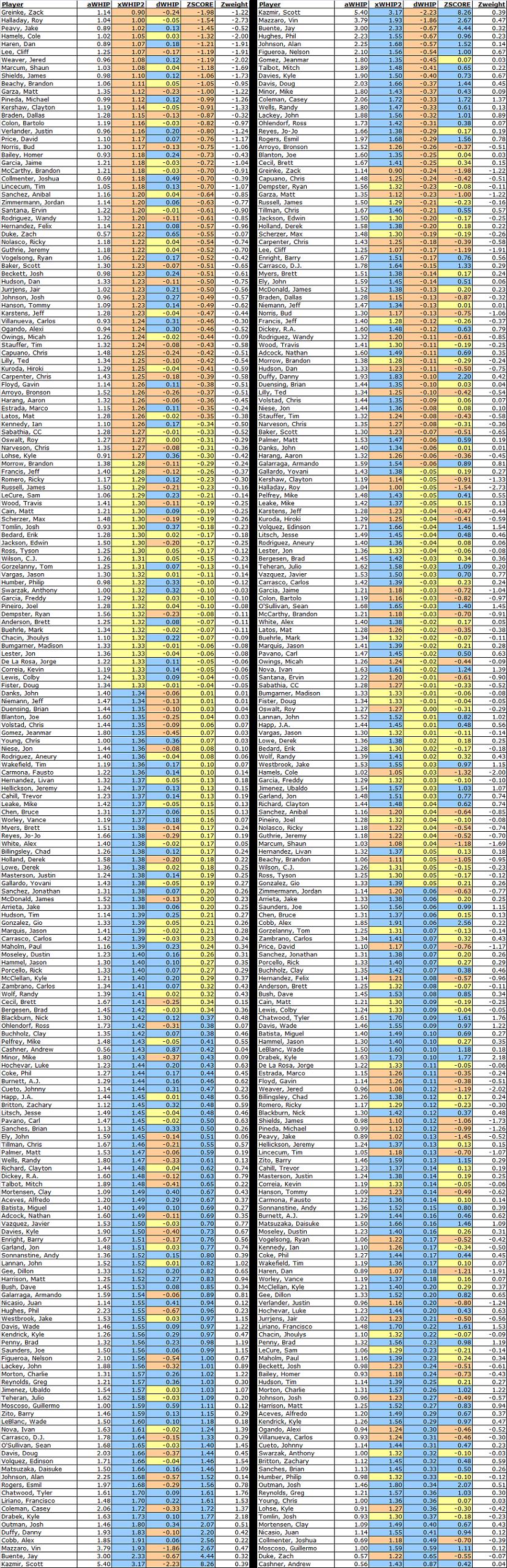

That said, let's look at the data. In case you have not already, you can download the spreadsheet by clicking here. If the column header has an "x" in front of the stat, it is xBABIP adjusted. If there is no "x," then that stat is the player's actual 2011 stat. For example, "AVG" is the player's 2011 batting average, whereas "xAVG" is his expected batting average based on xBABIP.

If the column header has a "d" in front of the stat, then it is a differential. For example "dBABIP" is the difference between a player's xBABIP and actual BABIP.

Looking through the 275-player spreadsheet, only 61 players (22 percent) have xBABIPs below their actual BABIPs, a testament to another year of excellent pitching and defense. The average actual batting average of the player sample is .267, while the average expected batting average was .281.

Clearly the data are a bit skewed on the high end. I tested the data set with slash12's xBABIP formula, and it also had an average expected batting average that was more than .10 points above the actual league batting average. Fewer than 30 qualified players had a batting average of or above .300 this year; xBABIP believes that that number should have been 42.

Turning to the data, let's first look at the "unluckiest" batters of 2011—those who are most likely to see the sharpest batting average improvements in 2012 (dBABIP greater than .050):

LastName FirstName Team BABIP xBABIP dBABIP

Chone Figgins Mariners 0.215 0.314 0.100

Vernon Wells Angels 0.214 0.298 0.084

Rafael Furcal MULTIPLE 0.240 0.320 0.080

Chris Coghlan Marlins 0.263 0.331 0.068

Ian Kinsler Rangers 0.243 0.310 0.068

Russell Martin Yankees 0.252 0.318 0.066

Logan Morrison Marlins 0.265 0.328 0.064

Casey McGehee Brewers 0.249 0.313 0.064

Jonathan Herrera Rockies 0.273 0.337 0.063

Evan Longoria Rays 0.239 0.302 0.063

Alex Rios White Sox 0.237 0.299 0.062

Hanley Ramirez Marlins 0.275 0.337 0.062

Dan Uggla Braves 0.253 0.314 0.061

Ben Revere Twins 0.293 0.354 0.061

Ty Wigginton Rockies 0.271 0.330 0.059

Orlando Cabrera MULTIPLE 0.259 0.318 0.059

Adam Dunn White Sox 0.240 0.299 0.059

Jason Heyward Braves 0.260 0.318 0.058

Mark Teixeira Yankees 0.239 0.296 0.057

Jorge Posada Yankees 0.262 0.317 0.055

Miguel Tejada Giants 0.254 0.308 0.054

Juan Uribe Dodgers 0.245 0.299 0.053

Kelly Johnson MULTIPLE 0.277 0.330 0.053

Adam Lind Blue Jays 0.265 0.317 0.052

Wilson Valdez Phillies 0.288 0.338 0.051

Coco Crisp Athletics 0.284 0.335 0.051

As you might expect, a lot of the guys with some of the lowest batting averages in baseball populate this list. Those players, though mostly terrible, were not nearly as terrible as their batting lines from last year indicate. For example, Alex Rios was likely more a .260-.270 than a .227 hitter, and Adam Dunn should have hit closer to .200 than .159.

Mingled in with the bad players with bad luck last year, however, are a few really interesting names. The one that most stands out is Ian Kinsler, who I already explained could be a first-round caliber player next season. In addition to Kinsler are Evan Longoria and Hanley Ramirez. Long-time fans of the pair can take a cautious sigh of relief if they were worried about spending a third-round pick on either. Mark Texeira is on this list, but I am more skeptical than I am with Ramirez and Longoria that he can bounce back to previous batting average form.

The most shocking name on this list might be Chone Figgins, who seems to be at the end of his career after a .302 wOBA (88 wRC+) last season and a putrid .218 wOBA (34 wRC+) this season. xBABIP thinks Figgins should have hit .273/.321/.332 (.653 OPS) this year, which would have been about league average by wOBA standards once park factors are considered.

Figgins' bat is pretty hollow in real life, but as a perennial base-stealing threat when he gets on, it is encouraging to see that Figgins still has the potential to get on base 33 percent of the time. Figgins' walk rate this season plummeted to a career-low 6.7 percent after four seasons of a walk rate above 10 percent, so some bounceback could be imminent just from regression. This noted, Figgins could be a sleeper source of stolen bases next year.

Next, the 26 "luckiest" batters of 2012 (dBABIP less than -.015), who are most likely to see the sharpest batting average declines in 2012:

LastName FirstName Team BABIP xBABIP dBABIP

Wilson Betemit MULTIPLE 0.391 0.323 -0.068

Adrian Gonzalez Red Sox 0.380 0.333 -0.047

Nick Hundley Padres 0.362 0.317 -0.044

Alex Avila Tigers 0.366 0.326 -0.041

Miguel Cabrera Tigers 0.365 0.324 -0.041

Hunter Pence MULTIPLE 0.361 0.322 -0.039

Chase Headley Padres 0.368 0.329 -0.039

Jose Reyes Mets 0.353 0.319 -0.034

Matt Kemp Dodgers 0.380 0.345 -0.034

Daniel Murphy Mets 0.345 0.311 -0.034

Victor Martinez Tigers 0.343 0.309 -0.034

Nyjer Morgan Brewers 0.362 0.329 -0.032

Jemile Weeks Athletics 0.350 0.320 -0.030

Michael Young Rangers 0.367 0.337 -0.030

Lucas Duda Mets 0.326 0.297 -0.029

Alex Gordon Royals 0.358 0.331 -0.027

Jhonny Peralta Tigers 0.325 0.300 -0.025

Dustin Ackley Mariners 0.339 0.316 -0.023

Andre Ethier Dodgers 0.348 0.326 -0.023

Carlos Beltran MULTIPLE 0.324 0.302 -0.021

Mike Napoli Rangers 0.344 0.323 -0.021

Joey Votto Reds 0.349 0.329 -0.020

Ryan Raburn Tigers 0.324 0.305 -0.020

Casey Kotchman Rays 0.335 0.318 -0.017

Michael Morse Nationals 0.344 0.328 -0.016

Ryan Braun Brewers 0.350 0.334 -0.016

As mentioned above, only 22 percent of the players in the sample overperformed their expected BABIP in 2011. This is likely due to the returned recognition of value provided by athleticism and defense in the post-Moneyball era, along with better pitching league-wide.

Unsurprisingly, the "luckiest" batters tend to be the guys who competed for the batting title, and in this regard we find the names Matt Kemp, Adrian Gonzalez, Victor Martinez, Miguel Cabrera, Jose Reyes, and Ryan Braun mingled into the list.

This does not mean that these players are per se guys to avoid next year; they are still great. Their inclusion on this list simply means that their value will be inflated above their luck-neutral talent line. An inflated batting average through BABIP luck tends to lead to extra runs and RBIs, as well as stolen bases, by virtue of the law of opportunity.

Some of the interesting non-elite names on the luck list are second basemen Jemile Weeks and Dustin Ackley. Second base was surprisingly deep this year. Per Yahoo's end of season player rankings, four of the top 26 players were second-base eligible, while seven of the top 100 players were second basemen. With both second base rookies poised to see their averages drop precipitously next season, it is quite possible second base might not be as bountiful next year.

Alex Avila also resides on this list. While his .295 batting average may not be for real, his 15-20 home run power is. The same can be said about Mike Napoli, who is really a .260 hitter with 20-30 home run power depending on playing time.

Of all the names on the list, however, I think Alex Gordon might end up being the most overrated for 2012. As a long-time Gordon supporter and well-rewarded 2011 owner, it pains me to call the guy overrated after years of him not getting a proper chance, but Gordon is not a .300/20/20 player.

Rather, he is more a .275-.280 hitter capable of a low .800s OPS with 20 home run capability and double-digit stolen base potential. A .280/20/13 campaign may be in the cards, but you'll likely be paying a premium over that level to acquire him next year in non-keeper formats. It is also worth noting that Gordon loses his third-base eligibility next year, which will also negatively affect his fantasy value.

So who are some names on the BABIP luck list that most shocked you? Who do you think is least likely to match his expected batting average?

As always, leave the love/hate in the comments below.